Telegram: Mats Gustafson / Reclaiming Beauty

An exclusive interview with the world's most prominent fashion illustrator

Mats Gustafson’s international career began in the late 1970s, when he showed his work to Vogue editor Grace Coddington, who promptly commissioned him to illustrate the fashion collections presented during Paris fashion week. In 1980, he moved to New York, where he is still based today. Through the years, he has worked extensively also with Vogue Italia but is best known for his longstanding collaboration with Dior.

He works with the French fashion house four times a year, by illustrating selected pieces from two haute couture-collections and two prêt-à-porter-collections (obviously, Dior produces more than four collections a year, but Gustafson only works on these four, adding, “I don’t know where Maria Grazia Chiuri finds her energy, constantly travelling the world for new inspiration”).

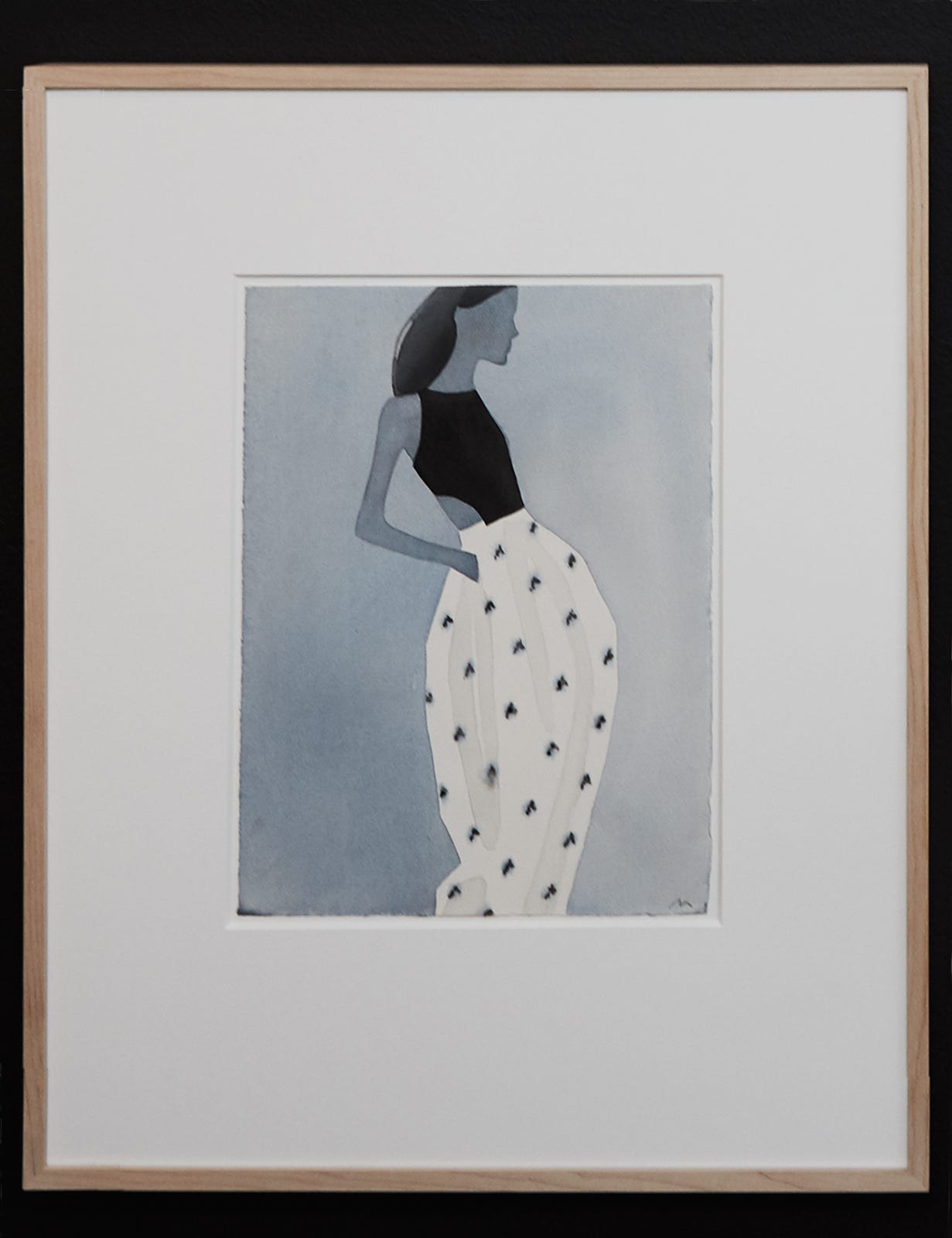

We met with him just before the opening of his new exhibition, “Reclaiming Beauty” in Millesgården, Stockholm. The exhibition shows Gustafson’s illustrations in tandem with designer Ted Muehling’s jewellery.

The raison d’être of the exhibition is to celebrate beauty and grace as a way of making everyday life more pleasant and meaningful. In the world of contemporary fashion, this is a defiant position that goes against much of what is in style at the moment, often designed for immediate online attention.

This approach is also what gives Gustafson’s work their radical edge.

Asked what he enjoys most about his creative process, Gustafson answered:

“The part I like the most is that I get to work by myself. I’m part of a team, but my task is to observe, and that suits me. It’s the observing that I like the most about my job. I’ve actually never answered this question like this before, but for me, it’s the observation that is at the core of what I do, in combination with the fact that it is quite an isolated process. If you compare being an illustrator to working as a photographer, you can see the difference. The photographer is bound to a certain place where he has to be at a specific time, interacting with a particular set of people. Obviously, I also have to interact with others, but not at all in the same way or to the same extent, and that suits me very well.”

Already at a young age, Gustafson knew that he wanted to work with fashion in some way. As for many other young people, fashion was an important part of his exploration of who he was and who he was in the process of becoming. This is one of the main strengths of fashion; it can manifest emotions and thoughts, turn what is happening on the inside into something possible for the wearer to communicate externally, so that other people can pick up on the message.

Growing up in a small town in Sweden, Gustafson first became interested in fashion through reading books on fashion history:

“I’ve always been amused by fashion and clothes, but also been interested in the history of fashion. And when I talk about history, I don’t mean specifically historical fashion, but the cultural history, the context that fashion has been a part of, like certain historical events. There is a history – and a story – in fashion that interests me. When I was a child, I was given a book called “Kropp och kläder” (Body and clothes) written by a Danish art professor named Rudolf Broby-Johansen. In this book, the professor demonstrated parallels between costume history and the history of the world in a way that I still benefit from, and that I rely on in my current role as an illustrator. So, in my creative process, in which I have to focus on the very latest in fashion, I also detect references back in time, to the past. This is of course not only true for the house of Dior, that I work with the most, but for fashion in general.”

“When you’re younger, fashion is a form of self-experimentation, but that part of life is behind me, so nowadays fashion is more something that I observe from a distance.”

In the most concise definition of the word, fashion is about change. It is because of this continuously ongoing change of styles that it is easy to distinguish one period from another. For example, the baroque era (of the 17th century) was aesthetically very different from the Belle Époque (in the late 19th century), and simply by looking at the fashion in portraits and sculptures, it is possible to date artworks. Fashion is a manifestation of life’s ephemerality and the fleetingness of existence, which is also something that Gustafson, with his vast experience, has pondered on:

“I always have the history of costume in the back of my mind. But I don’t anymore have the same sensitivity as I used to when it comes to the very latest trends. With age, you don’t really care as much about what’s in vogue or about what’s new at the moment, because you know it will be gone soon anyway. Sometimes, you unwillingly become a victim of a certain time period – and I think this is true for everyone – and later on you will look at old pictures, and you wonder why you dressed like you did, because it all looks so strange now…

When you’re younger, fashion is a form of self-experimentation, but that part of life is behind me, so nowadays fashion is more something that I observe from a distance. But there’s also another thing about fashion that has changed over time. I travel a lot between New York, Paris and Stockholm, and this made me very aware of the importance of street fashion. I’m sure it still exists, but today social media has become so dominant, and what happens there I don’t really know. The urban lifestyle is still there, but the digital aspect is happening simultaneously and is almost as important as fashion in the physical space. But social media is not my thing, so I don’t really have access to that part of fashion.”

Though Gustafson is primarily known for his work in fashion, he has also illustrated other worlds and types of objects, most notably scenes from nature. Regardless, he is hesitant to call himself an artist, instead preferring to see himself as first and foremost an illustrator:

“It’s not really important what you call your job, though at times I have been preoccupied with this question. But once I’m working on something it doesn’t matter what it’s called, how it’s defined, or where it belongs. It’s all the same process. Once you’ve begun creating something, it doesn’t matter if it’s an illustration of a swan or a dress. The need for concentration, and the hell that it entails, is always the same! Of course, I could have become a designer instead, but already as a teenager I decided I wanted to work with set design. Costume and scenography, to be specific. And I’m trained as a scenographer. But once I started drawing, I never stopped and I never looked back.”

Millesgården

Millesgården, where the exhibition is on display until mid-September, is situated on an island only minutes away from central Stockholm. It was named after the famous sculpture Carl Milles, who lived here with his wife Olga. They acquired the land in 1906, and two years later, the villa was completed. A few decades later, they bought the neighbouring plots and could thus expand the terraced sculpture garden into the large, labyrinth-like experience it is today, filled with hidden nooks and large artworks. In 1936, it was donated as a gift to the Swedish people.

Milles is famous for his many sculptures, commissioned by institutions around the world, often created with inspiration from the mythology of ancient Greece and Rome. For fifty years, he worked at developing Millesgården, today widely considered the most important artwork of his life.

To visit the sculpture park, regardless of season, is to catch a glimpse of the artist’s rich phantasmagorical landscape. Inside the couple’s mansion, the floors are full of beautiful mosaics, while the pink one-story building called Anne’s villa, built to house Milles’ private secretary Anne Hedmark and decorated by Estrid Ericson and Josef Frank, offers a completely different, more informal and relaxed atmosphere.

Olga Milles, born in Austria, was a painter and sculptor in her own right. In the meeting between the Austrian Olga and the Swedish Carl, two cultures and aesthetic traditions intersected and merged. Consequently, a part of the garden is called “Little Austria”, which is also were the two are buried, in a wood chapel designed to emulate the type of road chapel common in Austria and southern Germany. It is often said that life has a way of imitating art. This is true also for this place, as inspiration for the chapel was found in Moritz von Schwind’s painting “Die Waldkapelle”.

The restaurant at Millesgården is not to be missed. And in the art hall, which houses various exhibitions all year round and is placed at the entrance to the garden, there is a small shop where one can buy miniature versions of Milles’ most famous works, including the very poetic “The Hand of God”, celebrating the metaphysical bond between humans and eternity.